The Wright siblings left a mark on the world with the victorious flight of their Wright Flyer in 1903.

The Wright brothers’ first plane trip on Dec. 17, 1903, endured only 12 seconds and updates on the accomplishment made it into just four papers the next morning. However, the spearheading, 120-foot (37 meters) flight in a delicate plane over Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, enormously affected the whole world.

Brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright didn’t innovate flight, yet their craftsmanship abilities helped them structure the mid-twentieth century similar a startup. Their creation of the Flyer, which was the first run, fueled, heavier-than-air, and (somewhat) controlled-flight airplane, united people and concepts more than ever. In only a couple of decades, their thoughts prompted the making of new aircraft in war, helped with the spread of products and people for globalization and prompted spaceflight — remembering putting the primary individuals for the moon in 1969.

Humble Beginnings

Prior to planes, humans flew in balloons, airships, and lightweight airplanes — yet never in an option that could be heavier than air. A few researchers tried lightweight flyers all through the 1800s, filling information tables with data about lift and drag, yet no lightweight flyers ran on power other than that given by the air. A steam-fueled plane worked by Henri Giffard flew effectively in 1852.

Stage 1 for the Wright siblings was to do a literature overview on the condition of aeronautical information at that point. In 1899, Wilbur composed this letter to the Smithsonian Institution, asking access to duplicates of all the previous exploration done:

“Dear Sirs:

I am a devotee; however, not a wrench as in I have some pet hypotheses concerning the best possible development of a flying machine. I wish to benefit myself of all that is as of now known and afterward if conceivable include my strength to help the future worker who will accomplish the last achievement.”

The brothers considered the hang-floating trips of Otto Lilienthal and work done by Sir Georg Cayley, the instigator of Aerodynamics. The Wrights picked the mind of Octave Chanute, an engineer who had attempted to invent a plane and the writer of the book “Progress in Flying Machines” (Dover Publications, 1894).

With the benefits earned at their bicycle store, Wilbur (the visionary) and Orville (the designer) set to construct a flying machine. The brothers began by building kites dependent on the flight mechanics of birds they had watched, at that point, proceeded onward to keep an eye on gliders.

The First Flight

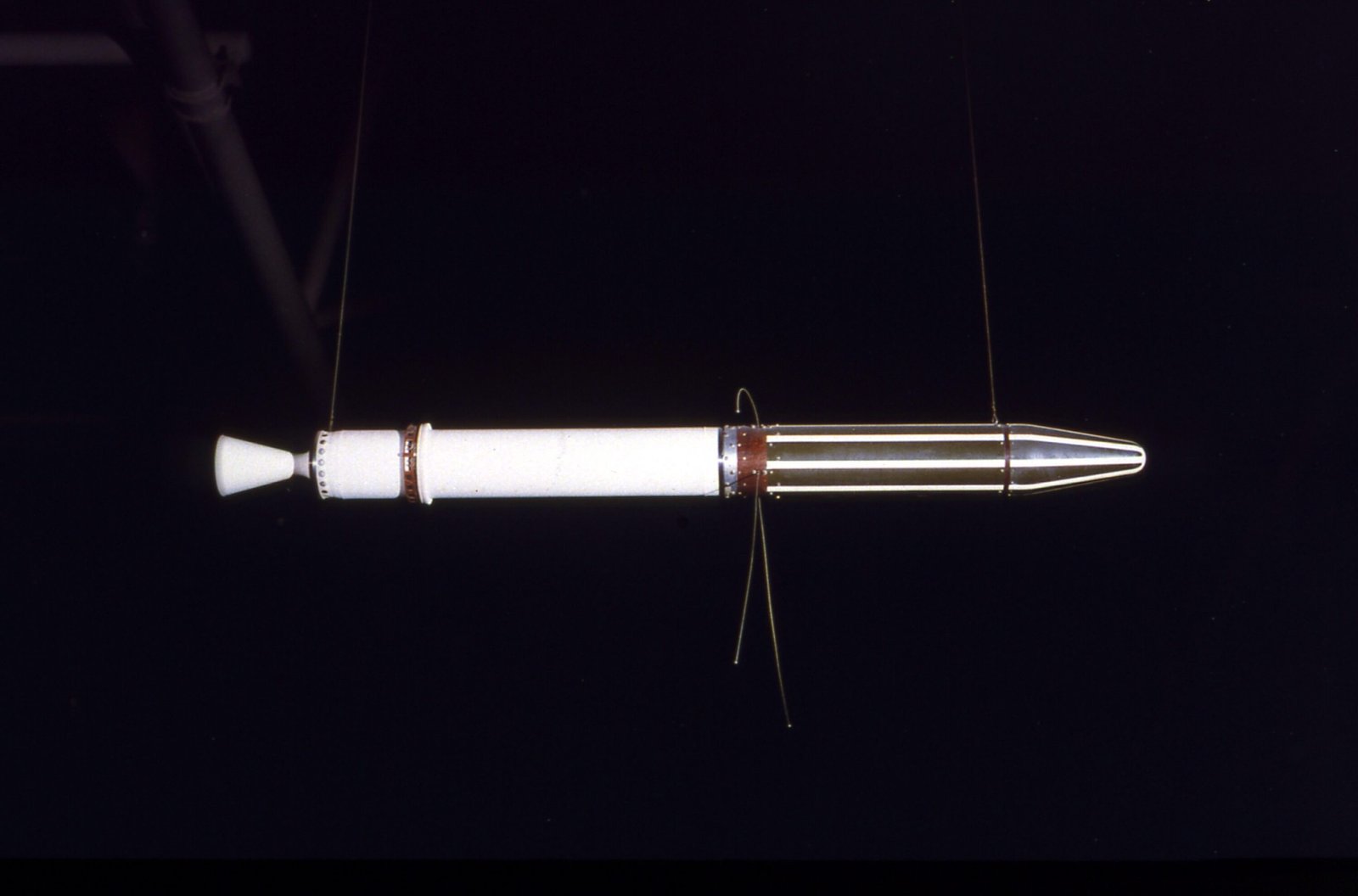

Four years after Wilbur’s modest letter, the Wrights were prepared to test an airplane fueled by a motor and propeller. The biplane configuration was based on Chanute’s biplane lightweight plane, and the engine was gathered by Charles Taylor, a technician in the Wright’s bicycle shop.

On Dec. 17, 1903, Orville moved into the crude cockpit. The Flyer lifted from the level ground of Kitty Hawk into the air and flew for 12 seconds before arriving with a crash 120 feet (37 m) away. Kitty Hawk was picked for its steady winds, which were useful for testing kites and lightweight planes and furthermore for taking off with an underpowered aircraft. While solid wind blasts could be perilous, a decent, steady headwind permitted a plane to take off when its own capacity probably won’t get it off the ground in windless conditions.

The brothers made four flights that day, the last one flying 852 feet (260 m) in separation and remaining on high close to 60 seconds, propelling the world into the flying age for good.

From Kitty Hawk to the outer environment

At the point when news about their success at Kitty Hawk arrived at the news wires, many keen investors endeavored their flying machines in cornfields around the globe.

It was the U.S. government that supported the first mass assembling of the plane, seeing the capability of an incredible weapon and surveillance vehicle. At the point when World War I broke out in 1914, there was another sort of war zone: the sky. Plane innovation accelerated drastically during the war and was a mainstay of the wartime economy.

By the 1930s, the U.S. had four airlines delivering a great many travelers (restricted generally to the high society) to focuses the nation over, over the Atlantic Ocean, and, before the end of the decade, over the Pacific. With the beginning of commercial air service, the world opened up in another way, permitting individuals to visit places they’d just found out about in books.

Aviation incredibly influenced the result of World War II, as well, and war similarly influenced flying. Planes conveyed paratroopers over the English Channel and dropped the main nuclear bomb. Before the finish of the war, the assembling of planes had assisted with putting the United States at the cutting edge of all the world after war economies, where it stayed until the 1970s.

The introduction of the fly age during the 1950s, American space travelers’ initial steps on the moon somewhere in the range of 1969 and 1972, and even the fantasies of room vacationer organizations like Virgin Galactic and oneself landing rockets of SpaceX all have their logical roots in the field of Kitty Hawk.

A Wright Flyer is in plain view at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. In 2003, a copy Wright Flyer endeavored a similar trip at Kitty Hawk on the 100th commemoration of the Wrights’ accomplishment, yet it fell into a mud puddle. Conditions were very quiet that day, and Tom Poberezny, leader of the Experimental Aircraft Association, which helped manufacture the reproduction, told Wired, “Well if this were simple, I surmise everybody would do it.”