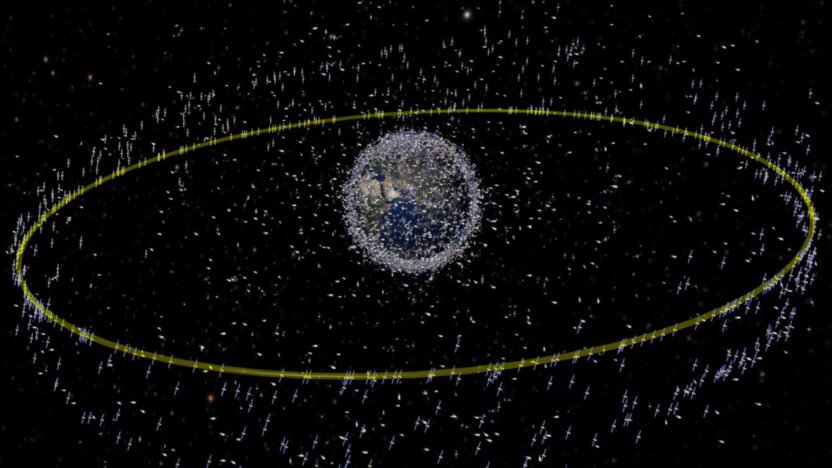

A recently issued Executive Order revises how the government implements Space Policy Directive-3, removing the longstanding expectation that basic space situational awareness (SSA) services, including conjunction warnings, would be provided without charge. This decision marks a departure not only from SPD-3, but from more than a decade of United States practice in which Congress and successive administrations supported the sharing of SSA information as a core safety function without directing agencies to charge for basic warnings. With that decision made, a more fundamental question comes into focus: What problem is charging for space situational awareness actually intended to solve?

There are three plausible objectives charging for SSA might be intended to serve: recovering operating costs, steering customers toward commercial options and deliberate ambiguity, each of which implies a very different theory of change.

The first is cost recovery. Under this approach, user fees would offset some portion of the government’s operating costs while Congress continues to appropriate the bulk of funding for civil SSA services. In practice, this model is unlikely to work. Given the current dynamics of the marketplace, fee revenue would be marginal, administrative overhead would be non-trivial and operators would retain the option of relying on free alternatives provided by other international SSA systems. Charging in this context would be disruptive to operator behavior without meaningfully funding the system.

A second possibility is market forcing. Under this theory, charging is not meant to fund government services at all. Instead, it is intended to push operators toward commercial SSA providers, accelerating market maturation through exposure to real demand and real failure. Some providers would succeed, others would exit, and the market would be expected to sort itself out.

This approach reflects a different, and questionable, sequencing logic than the one embedded in SPD-3. That directive assumed a trusted civil baseline would come first, followed by standards, confidence and commercial growth layered on top. A market-forcing approach reverses that sequence, using access to safety information itself as the lever of discipline. Whether that produces a robust market or a fragmented safety environment depends on conditions that have not been clearly articulated.

A third possibility is less deliberate but more concerning: strategic ambiguity. Charging is introduced without a clear determination of whether the government intends to remain a provider of baseline SSA services, evolve into a coordinating authority, or withdraw from operational roles altogether. Responsibility then shifts to operators by default rather than by design, forcing the market to guess at government intent. The result is not policy flexibility but governance failure: uncertainty for operators, hesitation by investors, and confusion for international partners about the U.S. role in space safety.

The problem is not that one of these approaches is inherently illegitimate. Reasonable people can disagree about the proper balance between public infrastructure and private provision. The problem is that charging means very different things under each model. Without clarity, it risks achieving none of the intended outcomes: insufficient revenue to sustain government services, insufficient trust to support commercial adoption and increased operational risk in the meantime.

The implications of charging for SSA

This ambiguity matters because space traffic coordination is not a conventional market. Collision avoidance decisions are time-sensitive, high-consequence and often irreversible. Operators rely on sources they regard as authoritative when maneuver decisions carry real financial and mission risk. Markets in such domains mature through confidence in standards, performance and accountability, not through price pressure alone.

Charging also affects operators unevenly. Smaller and under-resourced companies would face incentives to underinvest in SSA and to accept higher levels of risk, increasing systemic exposure in already congested orbits. Larger constellation operators may be better positioned to absorb fees, but they are more likely to respond by internalizing SSA functions and relying more heavily on proprietary systems. That outcome may appear rational from the perspective of individual firms, but it reduces transparency, data-sharing and shared situational awareness across the orbital environment.

There is also a legal dimension that cannot be ignored. Recent Supreme Court decisions have indicated that federal agencies may charge fees only where Congress has authorized them to do so, and typically for services that confer a specific benefit on identifiable users rather than the public at large. Space Policy Directive-3 expresses presidential policy, but it does not itself create fee authority, and Congress has not enacted legislation directing the Department of Commerce to charge for space situational awareness services. Treating collision warnings and traffic coordination as fee-based “special benefits,” rather than as a shared public safety function, rests on a contested legal foundation.

This is also a moment when norms for space traffic coordination are being set. The United States has long maintained that responsible behavior in space depends on transparency, cooperation, and shared responsibility. Providing basic safety information at no cost reinforces the idea that collision avoidance is a collective obligation. Charging for that information points in a different direction entirely, recasting safety as a market transaction rather than a shared norm.

If charging for SSA is the path the administration intends to pursue, it should be accompanied by a clear articulation of purpose. Is the goal cost recovery, market acceleration or a redefinition of the government’s role in space traffic coordination? Each choice carries different implications for safety, market structure, legal durability and U.S. leadership.

Policy works best when mechanisms and objectives align. Charging for space situational awareness without a clear theory of change risks turning a strategic decision into an experiment whose consequences will be felt not in budgets, but in orbit.

Richard DalBello is the former Director of the Office of Space Commerce.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.